Such an intense, yet "easy" narrated podcast from Thompson Owen @ Sweet Maria's Coffee. Especially from minute 5' to the 15th, plus the last 5 are brilliantly informing, honest and spoken from the heart, and should be compulsory for many coffee courses and trainings imho.

Have a view, listen and read!

Excerpts from Sweet Maria’s Coffee podcast

“Tanzania - A Moshi Morning Recording”

Part I | 5’23”

I realize when I travel in coffee there's just this I idea that I'm just immersed in this place and I'm having this really long interaction with these people here, but it'd be fair to say that I just breeze through in a lot of ways.

You visit somewhere, maybe you've been there before, but you spend like 30 minutes and like I try to compensate for that by recording everything and taking photos and paying a lot of attention and asking my questions and stuff.

But really, when you think about it, and that's why I think about how coffee buyers are tourists in a way, is that it's a really brief contact. And then you sometimes make the most out of it in terms of what you try to collect in information but also in photos you take. And then you represent like, you know, you were there and coffee people slip into this thing and [are] saying: “oh we work with this station” and it's like you visited 30 minutes you know, you buy their coffee that's not working with somebody.

And I don't want to take that too far critically but there's a lot of work in coffee and I do a lot of work. But it's not the work in actually producing coffee so when you say you work with a station or a farm they do a lot of work and I think it really trivializes it to use the word ‘work’.

I select lots and buy coffee from someone and it's important that they have a buyer but that doesn't need to be inflated to make it seem like you have a big project with them or you have a communication. You have a business relationship and I think that's accurate to say but ‘work’ is another thing. And I'm sure in one of these recordings I'm going to say ‘work’ but it'll stand out to me you know. I'm trying not to do that, I'm also trying not to say that I source coffee.

I just realized what I was thinking about something else, like sourcing, that kind of many interactions, that kind of connect with a particular coffee producer, like go back and forth, figure out how you're going to deliver coffee, coordinate it, get the coffee milled, select which lots and grades, do troubleshooting on quality; those are ‘the work’ of sourcing. And you just pretty much have to be in the country to do that work, you have to be there for the full season.

I would say that's the minimum, the qualifying bar to say: “yeah we source coffee”. I didn't go find these coffees like they exist and I don't do a lot of that back and forth and I'm not here for a long period of time. So ‘source’ is even an overreach in representing what my actual work is. So I decided that I'm a coffee selector. What I do is: people who actually do all the ‘work’ put options in front of me and I basically select which ones I want and which ones I think are good and which ones don't.

And that feels pretty accurate.

It's like [with] a lot of things, it's kind of diminishing in the role that I really actually play, but it feels a lot better to go that way then the way coffee companies compete in the language they use to continually kind of try to outdo each other in saying how much ‘work’ they do, how good they are, how close to the source they are.

I think just gently and not hypercritically, just let's roll it back a bit and try to be accurate and think about words we use. That's what I want to do and it just feels better, it feels more comfortable and I also feel it takes pressure off myself too, to describe my work that way.

The other way I've talked about myself is and what I do when I travel is that I'm a personal shopper. Like I don't buy these coffees for me, I buy them for my customers, so I'm here on their behalf to find really good coffee as best I can to make good choices. And you know, to try to find values, value in the coffee, I think some buyers feel just like some tourists feel. Like: “oh I can't haggle you know, I can't push back on a price someone gives me”, and then they're like resentful that they paid something.

(…)

It's kind of expected of you and if you're not comfortable with that [then] don't resent the fact that you just paid triple the price that you maybe should have. It's okay to negotiate on price with people, because I think it treats them with a kind of respect of being a business. Like you're a business, you know they can decide for themselves what they need and they're intelligent and know what they need to earn presumably. And if you just fairly say “hey this is 50 cents over last year, I know these costs went up, I know you're not asking for this because, but do you think we could meet in the middle, do you think you could do this?”

And to me that feels like fair and if they can't, they can't. I mean, I want to deal with coffee sources where their coffee is good and so if it doesn't work out with us, [then] they will have another buyer because they have something real to stand on. And it's kind of tricky because, I don't know, I feel like sometimes this idea of “you're helping farmers by buying the coffee” has a patronizing feeling.

It may feel like you're respecting them in a way, but I sometimes think it's the opposite. It's like you're doing something good and that's like charity. And that charity may ultimately not benefit anybody. It may in the short term, but if someone for example [uses it as] a cool story behind their coffee and [they] are buying it and then business fails, goes a different direction or something, just doesn't buy [anymore] from that country that year.

When they take their coffee out to sell it they're either going to have to find someone like you who's “charitable” or they're going to have to take a lot less money because their coffee maybe wasn't worth it of itself. So I think it's important on quality to be honest and I think having that as the basis of buying coffee can be pretty solid.

You know it's a real value that they can take to somewhere else and someone else and it'll be there for them so I don't think you know that's not like A or B, or yes or no. It's not really a perfect solution because I can see something kind of patronizing in that too but between two different approaches and buying coffee I think that's better for me, it feels a little better.

15’00”

Part II | 22’01”

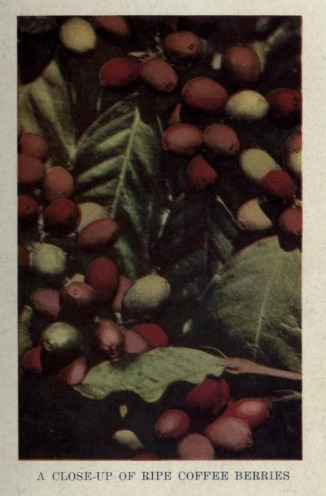

Talking about price like “what price are you paying?” You find this [in] a lot of places and even the marketing people are like “we pay a great price to farmers”. But it's volume that matters so much; if you don't have much coffee to sell, no matter if you get an amazing price, it doesn't do much. Growing, getting good production, having a lot of cherries on the tree, knowing how to treat trees well and having the resources to do that is so important and it's really something that I'm seeing all over here.

The fancier farm we went to yesterday that has good investment, that's really well organized, you can see that their production is really high, they're growing under managed shade trees, it's lush and beautiful. And you'll see other places with just no shade, spindly little trees, environmentally it's not very sound and for the coffee it's just not going to produce much. And even if they did have great coffee, which they probably don't, and got a great price it doesn't go very far you know.

If you have a thousand kgs to sell at a fantastic price it doesn't mean much in what you can reinvest in the farm, as opposed to having five thousand kgs that you sell at a good price and potentially some at a great price. So that's kind of on my mind here but it's nice to see this place and kind of understand the specific issues.

One of the things with coming to producing regions is that – you know [I was] just at SCA [Expo] a month ago and you hear talk about this and talk about that and what farmers need. But you come to specific regions and it's [when] you realize that like coffee in one place and coffee in another place are just not the same thing. There's a whole other way that you need to think about and talk about coffee and apply these sort of ideas that first of all doesn't just come from some [coffee] forum held in [a buyer’s country] by people that you know have the means to travel there or the position to travel there.

It needs to come from the location itself an, you know, it's great to have ideas come in that are from somewhere else and are fresh, but it's also important to have ideas bubble up from the specifics from “what do coffee farmers need here?”.

(…)

I just think there's a kind of hubris and the way coffee gets talked about uniformly and unilaterally. And just as the singular thing, and coming to a producing region, I think one of the reasons travel and coffee is good and enriches [a] person's understanding of it is the specificity of each place, [of] getting that context and understanding how [and] what coffee is here, is not what coffee is somewhere else.

And a coffee farmer here is not a coffee farmer somewhere else, and that's why the local agronomist to me is one of the most important people because they bring in knowledge and expertise but they're always trying to look at the context in order to find out what actually works on the ground and what people will actually do which is probably the most important thing of all.

So yeah…

– 26’48”